A Walk of Remembrance for the Chinese Community in Monterey, CA

The city where immigrant grit became beachfront glamour

From a Chinese fishing village to Cannery Row and a Methodist retreat, the city of Monterey, CA has evolved into a world-class wonder.

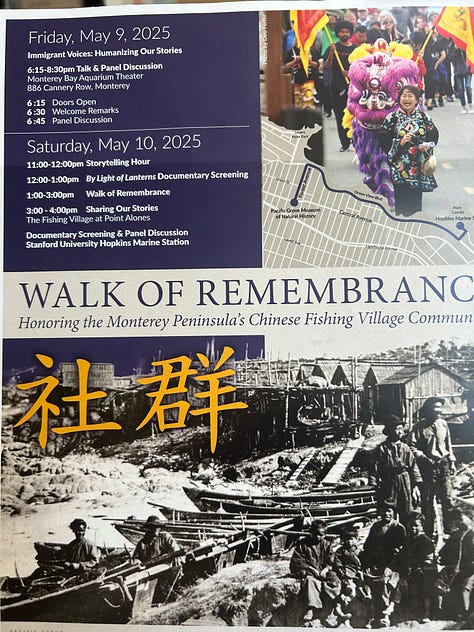

On May 10, 2025, I participated in the 15th annual Walk of Remembrance to honor the Chinese Fishing Village communities on the Monterey Peninsula [co-sponsored by the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History and the Quock Mui Foundation). At Monterey Bay the Aquarium theater hosted a talk and panel that shared immigrant stories.

While speaking with organizer Dr. Floyd Huen, a resident of Monterey and founder of Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley, and past President of the of Associated Students of University of California (1969), he emphasized that without this annual march, the origins of Monterey’s Fishing Village and the contributions of the Chinese would fade into obscurity. Here are some of the stories they shared:

Sampans from China

In the early 1850s, five sampans from Guangdong, China, set sail for the rugged coast of California. Only one boat survived. Nursed back to health by local Indians, the Chinese found a wealth of abalone lying in an ocean bed teeming with other sea resources. Using traditional methods brought from their homeland, the fishing families met with quick success. Soon other Chinese joined them and helped established the first commercial fishing industry in Monterey Bay. The settlers built wood houses along a small cove sheltered by two rocky points, sandwiched between today’s Stanford Hopkins Marine Station and the Monterey Bay Aquarium. By the 1870, a full-fledged fishing village had grown.

The village soon became the regions’ cultural capital.

Chinese migrants were the first group to establish commercial fishing in the Monterey Bay. They began with abalone – the Villager at Point Alones (“Abalone Point”). Focused on drying and selling abalone meat. They also began selling the shells. The ocean swarmed with abundance of cod, flounder, halibut, mackerel, rock fish, red and blue fish, yellow tail, sardines.

Little would they know that future marine scientists would distinguish this area this way:

“nowhere in was there a more important body of water, at least from the scientist’s point of view than Monterey Bay, both for the number of fish and other sea animals found here and from the fact that that there are many kinds found here that have never appeared in any other part of the world”

—David Starr Jordan, President, Stanford University from “Beasts and Fishes of Monterey Bay,” San Francisco Call (Nov. 9, 1901).

(The Monterey Bay Aquarium opened in 1984, is considered one of the top aquariums in the U.S.)

Soon, other fisheries for markets in San Francisco, and China grew and were developed. The Chinese villagers dried most of the fishes they caught and shipped them out of Monterey along markets as far as Salinas, Gilroy, and San Jose.

In 1850 or 1851, the Chinese immigrants to America founded California’s salt-water fishing industry, an industry to which they were contributing several hundred thousand dollars annually. Between 1850 and 1941, there were over 30 Chinese fishing villages in San Francisco, stretching from San Jose in the south to Marin and Contra Costa counties in the north. The number of Chinese fishermen on the bay was well over 1,000. And possibly as high as 3,000-4,000 during the season.

Forced out of Day time Fishing – turns to Squid

The Chinese were never allowed to pursue their occupation in peace. Lobbied by anti-Chinese sentiment, the State legislature instituted a monthly tax of $4.00 on all Chinese fishermen in 1860. At a time when the average fisherman netted $20-$30 a month during fishing season.

The Chinese villagers also met with a strong, often violent Anti-Chinese Movement. New immigrants to the Monterey Bay included Portuguese and Italians who began to take over the fishing grounds established by the Chinese. However, ever resourceful, the Chinese then began nighttime fishing for a new resources: squid.

The squids are attracted by light. The fishermen equipped their small sampans with “fire baskets” suspended by a long metal pole from the bow. In these “fire baskets” pine wood was burned. When the squid is drawn to the fire, they swim to the surface and then scooped up by nets.

The larger squid from a nights catch would be split, cleaned and salted then placed on racks to dry. Packed in barrels with salt, these squid were shipped to China for use as a snack, food enhancer or fertilizer.

Cannery Row

“Squid season” began in May. Settlers complained about the strong and unpleasant smell of drying squid. “When the fishing is good, acres of ground around Chinatown will be plastered with this fish”. Fishermen were extensively engaged in drying fish, spreading them on tables from a hundred to a hundred and fifty feet in length and turning them each day until thoroughly dried. A petition protesting the practice adopted by the Chinese of drying squid in the neighborhood prompted action. The new town of Pacific Grove even passed a ban on squid drying fields. But the Chinese continued.

In 1905, the Pacific Improvement Company (PIC) refused to renew the villagers' lease. In 1906, the great earthquake struck, and the Chinese village burned to the ground. On May 16, 1906, the Fishing village at Point Alones, burned down mysteriously. No explanation was given. The Chinese were barred from returning to retrieve their belongings or allowed to rebuild. A Monterey resident named McAbee offered the villagers his small cove. The new McAbee Beach village lasted until the early 1920s, where Cannery Row had its roots. The Chinese then took jobs in the canneries and started new businesses.

Quock Mui - the “Spanish Mary”

Born in Point Lobos, Quock Mui (1859-1936) was known as the first documented Chinese American female born in the Monterey Peninsula area. She had an amazing talent to speak five languages. Spanish speaking people would ask Quock Mui to help translate for them. The Quock family and other Chinese built little cabins on the northwest side of what is now called Whalers Cove In Point Lobos State Reserve where they made a living by fishing. Her extraordinary skills as a linguist often put her in demand as a go between among members of different ethnic groups in the city. The house she inhabited as an adult still stands near Cannery Row. Her descendants still live in California.

Gerry Low Sabado (1949-2021)

Gerry was a fifth generation descendant of Quock Mui. In Spring of 2011 Gerry Low Sabado and her husband Randy collaborated with the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History to create the Walk of Remembrance.

While carrying portraits of descendants, participants walked the mile-long from the Museum to the site of the former village at Hopkins Marine Station.

“I’m trying to open people’s eyes to the real story and struggle that happened right here. For too long, residents and tourists have been unaware of the rich history of the Chinese immigrants in the Monterey peninsula, particularly in Pacific Grove, the adversity, and the racial discrimination they faced.”

- Gerry Low Sabado

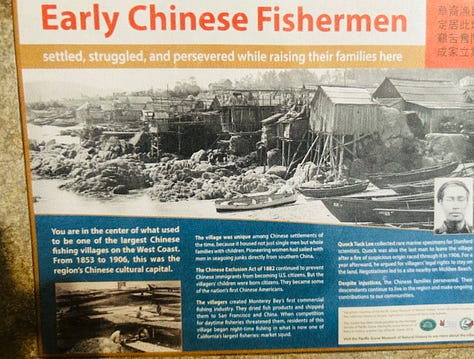

On September 20, 2014, the Heritage Society of Pacific Grove dedicated an 18 x 23-inch porcelain-enameled plaque that tells the story of the village. The plaque was set into a boulder on the rec trail across from the American Tin Cannery and between the Hopkins Marine Station and the Monterey Bay Aquarium, where the village once stood.

In 2022, the City Council of Pacific Grove passed Resolution No. 212-024 officially apologizing for the City’s role in the mistreatment of the Chinese community. The resolution recognized the injustices suffered by those whose homes were destroyed, voices silenced, and history obscured.

The walk has since become a powerful symbol of remembrance and education, embodying Gerry’s message of changing minds through kindness, offering an important step toward reconciliation and acknowledgment of past wrongs. “It’s a tremendous story about perseverance”.

Pacific Grove – the Early Years

In 1874, Reverend J.W. Ross, a Methodist minister and his wife visited the site and decided that this would be an ideal location for a proposed Methodist retreat.

“One day – I shall never forget it - I had taken a trail that was new to me. After a while the woods began to open the sea to sound near at hand. I came upon a road and to my surprise, a stile. A step or two farther and without leaving the woods,

I found myself among a magnificent grove.

It was just beautiful, that’s all. Wild lilac in those days was everywhere. Of course it grew wild. There’s a little wild lilac around the Peninsula yet. But the odor from the wild lilacs was like a perfume bottle in those days. And then the butterflies, like the butterflies that are here now, they were here in, oh, much greater quantities than they are now. They would settle on pine trees. The trees that they selected, you couldn’t see any foliage hardly at all-just one solid mass of hanging butterflies, thousands of them.”

- Adam W Weiland, “The Way We Were” in Pacific Grove the Early Years (Chamber of Commerce, 2000)

Captivated by the radiance of its glory, they selected this site as the first Methodist summer retreat. The location near the butterfly grove functioned as the Monterey Peninsula’s first “gated" community, featuring a padlocked gate positioned at what is now the intersection of Lighthouse and Grand Avenues.

This gated camp retreat insured an adequate and secure separation from the vices associated with the nearby township of Monterey. The first rules and regulations were published reflecting the Methodist influence. Among other things, these early rules prohibited intoxicating beverages, gambling, dancing, profanity, smoking, firearms, and curfew laws.

The community established blue laws that rejected many common practices among the residents of the Chinese fishing village - such as gambling and smoking opium.

As more and more worshippers became attracted to this retreat site, the founding fathers of the mushrooming Chautauqua tent town on the Monterey peninsula began plans to lay the cornerstone for their new church.

The Chautauqua Movement, a part of the Methodist Church, was instrumental in promoting education and cultural enrichment in the establishment of museums. [See Chautauqua: The Nature Study Movement in Pacific Grove, California]

In June 21, 1888 an enormous Methodist edifice rose above a small pine grove, called Pacific Grove. A cornerstone was laid for a Methodist church to be used not only for worship but for the concerts, lectures and classes which had been offered at the seaside camp since 1879.

One such class included summer camps and a mission school.

Chinese Mission, Point Alones

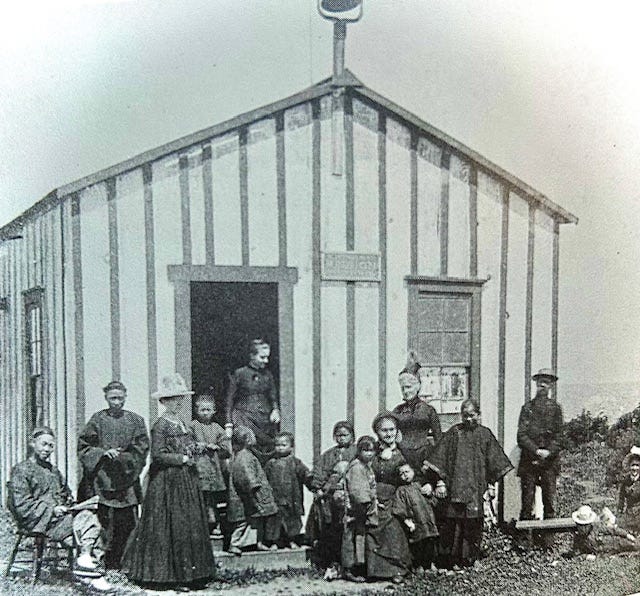

The Chinese fishermen had settled in the area two decades earlier than the Methodists, yet they were not permitted to attend public schools. When the Methodist Episcopal Church established the Chinese Mission at Point Alones village, it was conducted in a small school building on the coast, just west of the fishing village. Mrs. Eunice Wilson, member of the Women's Foreign Missionary Society, was the first to extend help to the children of the Chinese fishermen. In 1883, she founded the Chinese Mission at Point Alones. In 1890, after the building lease expired, Mrs. Wilson relocated the school to Pacific Grove. This was the only educational opportunity available to the children of Point Alones fishing village. From 1883 to 1890, enrollment averaged twenty or more students. After Mrs. Wilson’s death in 1894, none of the Protestant missionary organizations could be persuaded to take over the mission. However, the Word of God had been established and slowly began to take root.

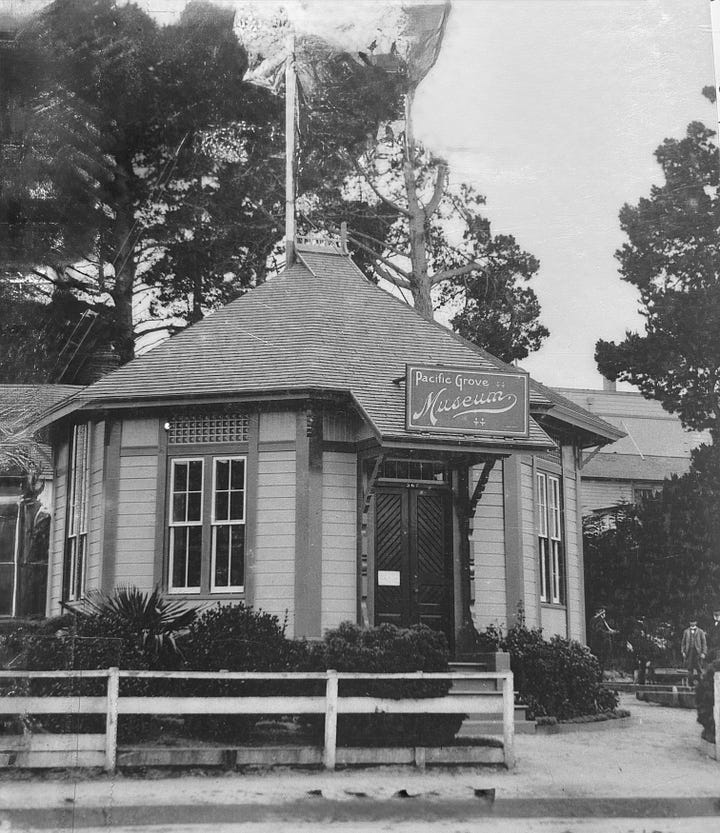

Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History

The Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History has strong roots in the Methodist Church retreat that established Pacific Grove in 1875. The museum was directly founded in 1883 by the Methodist Church’s Chautauqua Movement.

In short, the museum’s creation was a direct result of the Methodist Church’s influence on Pacific Grove, which began as a religious retreat.

Settled, Struggled, Persevered

The Chinese had arrived in Pacific Grove nearly two decades before the Methodists. They settled, struggled, and persevered while raising their families here. Yet, they were not permitted to own or hold title to property or become American citizens due to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Founded by a handful of immigrants in 1850’s, Pacific Grove’s Point Alones Chinese Fishing Village was the largest Chinese settlement on the Monterey Peninsula. From 1853 to 1906 this was the regions cultural capital. It served as the cultural and social home base for many of the Chinese living in Monterey. That the Chinese remained and thrived was recognized as unique. It is one of the few Chinese communities in California where entire families of men, women, and children lived and worked for several generations.

The Chinese remained and thrived because they strived with patience and resignation with an abiding hope for something better. Whereas other Chinese communities received only single men as residents, these Chinese families intended to stay and established strong family support. Due to their perseverance and hard work, the Chinese were the first to recognize the potential for commercial fishing in Monterey Bay. Through the Chinese knowledge in harvesting processing and drying the Chinese fishermen pioneered the development of the west coast abalone industry.

The Chinese abalone fishing industry began as a large-scale export industry that contributed significantly to the development of California. To this day, the Monterey Chinese Fishing Village descendants continue to live in the region and make ongoing contributions to our communities and overall U.S. fishing industry, both spiritually and economically.

Where the presence of the Lord established, the Spirit of the Lord flows.

References

Vince Bradley, “Methodists Open 1888 Cornerstone in Pacific Grove” (unsourced newspaper article dated 1963). Article clippings are from the Pacific Grove Public Library archives (Monterey, CA).

“Chinese Fishing Village Exhibit,” Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History.

Michael Kenneth Hemp, Cannery Row, 4th Ed. (Gig Harbor, WA: The History Company, 2019)

Laura A. Lee, “History Rewritten: The Story of Quock Mui Jeung,” Asian Pacific American Law Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring 2006), 75-91.

A.L. Lundy, Real Life on Cannery Row (Santa Monica, CA.: Angel City Press, 2008)

“Mayor’s Proclamation,” Newsletter of the Heritage Society of Pacific Grove (June, 2012). From Walk of Remembrance (Temporary Exhibit) at the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History.

Lydon Sandy, Chinese Gold (Capitola, CA.: Capitola Book Company, 1985)

Adam W. Weiland, “The Way We Were: The Early Years,” History of Pacific Grove. From the Pacific Grove Chamber of Commerce and Tourist Center website. Accessed June 28, 2025 at https://www.pacificgrove.org/history-of-pacific-grove/

Claire Wong, “A Chinese Fishing Village Regains Its Rightful Place in California History,” Atlas Obscura (March 31, 2020).

Video | “By Light of the Lanterns” documentary (2004)

The documentary digs out the unknown history of Monterey's early Chinese fishermen, who built the foundation of commercial fishing around the turn of the century, through the eyes of a direct decedent of the first Chinese immigrants in the area.

Comments may also be sent to the Asian American Christian History Institute at aachi@fuller.edu.

From Peter T. Lam (Toronto, Canada):

Elgin Quan’s “A Walk of Remembrance for the Chinese Community in Monterey, CA” is an informative, interesting piece of writing. Its flowing style makes readers read it from beginning to end without stop.

After reading this article, I cannot help but admire the perseverance and resilience of Chinese settlers “whose homes were destroyed, voices silenced, and history obscured”. It was not just at Monterey Bay but everywhere in North America. Nonetheless, they were able to survive and make contributions, culturally and economically. At Monterey Bay, “culturally” was the Chinese fishing and food processing culture they brought.

Racial minorities, not just Chinese, often suffer from low self-esteem. They grew up in poverty. Their parents engaged in lowly jobs. They heard disparaging remarks. Articles like Ms. Quan’s can be a form of bibliotherapy for minorities. However, I am disappointed not to see a photo of “fire baskets” mentioned in the article.

Peter T. LAM, M.A. (Johns Hopkins)

Toronto, Canada

Informative, easy reading especially about Chinese in relation to the Methodist Church

In-depth, well documented research.